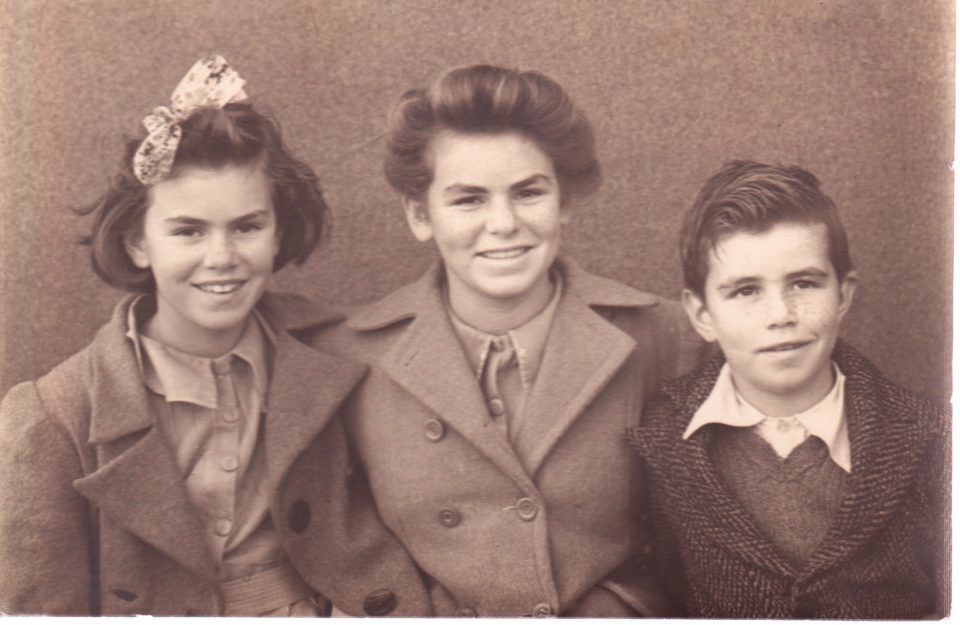

Noelene White, daughter of teacher Noel White, still remembers today her family’s arrival at Carrolup in 1946. Here is a description based on an interview I had with her which you can find in our book Connection: Aboriginal Child Artists Captivate Europe.

“Noel, Lily and their three young children—Noelene (now 12 years old), Janette (known as Jenny, 10) and Ross (7)—travel down to Carrolup from Narngulu in May 1946, a trip which involves two long train journeys and a drive from the railway station in Katanning. Their journey becomes all the more adventurous when their Morris Cowley Utility car, which has been transported to Katanning on the trains, loses a wheel close to their destination.

No injuries result from the accident and the Whites are able to walk to a local farm, owned by Mr and Mrs Beneky, who provide them with a hearty lunch, and then telephone Carrolup. A Mr Beasley arrives in a car and transports the family to the Settlement. The White children sit in the car whilst their parents go into the superintendent’s office. The car is surrounded by a large group of Aboriginal children, all staring through the car windows at the white children.

Noelene White takes up the story. She remembers clearly this day from over 70 years ago.

* * *

‘As we approached the Settlement, we saw a scattering of buildings in an area surrounded by bush. We pulled up in front of the superintendent’s office, which was at one end of a long flat wooden building with a veranda. The rest of the building was the Settlement store. I remember that the dirt road in front of the building had been meticulously raked with a hand rake—there was not a leaf in sight. We later learned this raking had been done in honour of our arrival by Alec Rowe, one of the black trackers (I use this term with respect as this is what they were called in those days). Alec was a son of Tommy Windich, the famous Aboriginal explorer.

I’ll never forget that first time we rolled into the Settlement. There were lots of Aboriginal children standing, sitting around, or hanging off anything they could climb. It felt like hundreds of pairs of eyes were staring at us, the new arrivals. Of course, they were wondering what their new teacher would be like. For now, their new teacher and his wife were meeting the Settlement superintendent, Mr Kenny.

To us children, there was something very strange about the Aboriginal children. I remember this occasion with great clarity, as did my siblings. All the Aboriginal children seemed to have ‘candles’ hanging from their noses. A horrible shade of green candle, ending in their mouths. (We later learned the children had colds and respiratory problems and there was no such thing as tissues or anything else).

The children all had severely matted hair and were filthy dirty. They were wearing some kind of faded clothing, but had no shoes. It was a bit frightening to see so many shades of black skin. Remember, we had hardly ever seen an Aboriginal person around Narngulu, so it was a bit of a culture shock. We wondered to what we had come.

We were in for some more shocks! There was no house for us, as had been promised. We were to live in two rooms in the Staff Quarters, a wooden building more or less in the centre of the Settlement. Our mum was not too pleased with these arrangements, but said nothing at this stage. In fact, all our family wanted was a house of our own, as promised.

Another shock was the smell! A dreadful acrid body odour, an indescribable smell. Something we had never before encountered, and it seemed to permeate everything—the food, the chairs, our clothes, just everything. We felt sick from it. We soon learned it was the odour of unwashed Aboriginal people. Mind you, when we talked to some Aboriginal people about the smell, they told us that they reacted in the same way to the smell of white people!

Mum soon said she had had enough. Dad did some scouting around to see if there was any kind of dwelling that could be made liveable. The only place that might be made liveable was the disused morgue. It was a wooden and asbestos building comprising two rooms, with a washhouse and toilet a short distance away in the backyard. The rooms were full of dust and rubbish and had been used to ‘lay out’ dead bodies before burial. It had possibilities!

Dad got approval from the superintendent that we could move in. He was assigned a few young men, and between them they had everything taken out and the place swept out in a short time. Dad built a small kitchen and bathroom behind the two front rooms, and a sleep-out (covered verandah) three quarters around the dwelling. Now Mum came on to the scene, and being the ‘arty lady’ she was, she had all sorts of ideas as to how this place could be made into a lovely little home for us.

I should mention that there was no electricity, which meant no lights—we survived with Tilley lamps—and no refrigerator. Although Dad had ‘modernised’ the bit of a washroom we had out back, we still only had cold water. And it was freezing cold in winter. The water supply at the Settlement was also very poor.

Our residence was no bed of roses; in fact, it was really primitive. All I can say is that we had a bed to sleep in, and a table and chairs for eating, plus our lounge chairs and other furniture we had brought from our old home in Narngulu. There was a Metters wood stove in the kitchen, on which mum cooked, and an open fireplace in the sitting room, which provided much needed warmth in winter. The main thing was that we were together as a family and that awful smell was gone.’”