Here is a copy of the Address that John gave to the Rotary Club in Kojonup on 28 October 2021, after being invited by Alan (‘Bear’) Warburton. NB. Click on small images to increase their size.

I have come to this meeting of Kojonup Rotary with a deep sense of appreciation.

Not only have I been here before, in April, and enjoyed the depth of your hospitality then; but now you have invited me back.

This time, I have been asked by Bear to give a talk to you all, no less.

*****

However, I’m going to give an address on a rather different topic—not my hobby-horse about the Aboriginal Child Artists of Carrolup, as I’ll be talking that tomorrow night at Kodja Place.

Tonight, though, I’ll be talking on something about me.

Who am I?

And why am I here, in Australia?

People often ask me why I have, as a Kiwi, spent my entire career working with Australian First Nations people—both through research and through my position as Director of the Berndt Museum of Anthropology at The University of Western Australia?

I will answer this question in four parts:

FIRST

I think that I was born to be a Social Anthropologist.

In Social Anthropology, there are no bones, and no digging—just talking with people, trying to understand how people live.

And learning why and how they ‘tick’.

With Caroline Stanton (‘Nanna’), walking up Queen Street, Auckland, near the Central Post Office. 1953.

I remember, as a child, walking up Queen Street with my paternal grandmother, Nanna, thinking about people, who they were, where were they going, grabbing a tram. This is before the trams were taken out—now, they’re thinking of reintroducing them, all these years after.

And then, so many years later, being in Sixth Form at Pakuranga College, at Howick (now an Eastern Suburb of Auckland, NZ) in 1967 having, in my final fortnight, free time. There was an ‘Accreditation’ system there, back then, whereby students could obtain their Matriculation (University Entrance, as it was called) based on their term marks, rather than by examination, if only to relieve the burden on university staff in marking.

So, for the two weeks of examinations, instead, we were obliged to attend school but, instead of attending classes, we had a different guest speaker each morning (the afternoons were spent doing a subject option that we had not taken, e.g. horror of horrors, dissecting a pregnant rat in Human Biology).

One morning, we had a person come to speak with us about the discipline of Anthropology. He was a Lecturer from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Auckland, himself Māori, Dr Pat Hōhepa. As soon as he started to speak about Anthropology, and in what it was less than five minutes, I knew that this was the way I had been thinking all my life.

It was, indeed, a life-changing moment.

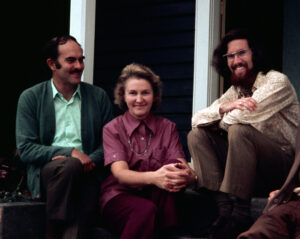

With my parents, Peter and Shirley, on the front steps at Howick, New Zealand, the day I left to live in Perth. 1st March 1974.

I spoke with him privately after his talk, and he invited me to visit him at the Department the following year to meet some of the staff and the students there, that year being my ‘Upper Sixth’ as it was then called, later ‘Seventh Form’ and now Year 13. I met up with him again at the Department a few months later and enrolled in First Year Anthropology as soon as I left High School at the end of 1968.

I’d found my forté very early, and I was very young (I was to turn 19 that year).

And this is how my career began.

I did my Bachelor of Arts for three years, majoring in Anthropology, with Māori as my ‘foreign’ language and Statistics as the ‘mathematics’ component, both required for the B.A. in those days.

I then did a two-year Master of Arts by research, conducting field work with Aboriginal fringe-dwellers and itinerant fruit pickers at the back of New South Wales just over the state border from Mildura. I recorded interviews with both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, a practice I continued when I moved to Western Australia to study, for my PhD under Professor Ronald Berndt, community dynamics at Mt Margaret Mission in the North-Eastern Goldfields, on the edge of the Western Desert cultural bloc. And I submitted a 16mm film as part of my Masters thesis, too. A first for New Zealand.

SECOND

I was fascinated with processes of social change.

I think this stemmed from a general interest in history, especially social history, from a relatively early age. I was interested in old things, like the design of old houses, and I liked old people, whom our mother encouraged us to talk with.

On a field trip to Mt Margaret with Sonja Scherini, taking some of the Shaw children to swim in the water tank. January 1983.

I joined our local Howick Historical Society at the precious age of 15 (most of the members were ‘ancient’, I remember), helping, among other things, to excavate the well of an early colonial (1847) inn, and started to learn, with others, the arts of building restoration.

But at our own home, there were always elderly widows and widowers at the Sunday lunch table, each with their own stories, their own experiences, and their own perspectives.

For example, there was one old man who lived up at the corner of our village road, who had been in the Boer War. He had lied about his age at the time; he was just 14 instead of the required 16, and became a ‘donkey man’. My family and I heard often all about his life during the Boer War.

Another old man was old enough to remember watching the Wright Brothers demonstrate their prototype aeroplane above the cliffs of Dover. For me, that was wondrous. Right back at the very beginning of heavier than air transport!

These are just two examples; there are many others, but these two particular, and very different, life stories have always stuck in my mind.

I guess my early realisation that history was essentially social, about lived experience, enhanced my appreciation of the discipline of Anthropology, which has a very similar focus; learning about others, and appreciating these people’s experiences and thoughts.

Anthropology, though, has some specific techniques and applications.

For example, it is essential to work directly with people.

Sorting artworks in the Berndt Museum purchased a month earlier on a field trip to the Kimberley. August 1999.

We can learn a lot from reading books, even reading archives, but there is nothing better getting the story directly ‘from the horse’s mouth’, so to say.

Anthropologists use notebooks, and more recently tape recorders, and now video cameras, to record people’s stories and perspectives. There is a certain veracity in direct face-to-face recording that would overwise be lacking. There is, of course, no one ‘truth’, as everybody sees the world through their own eyes, and interprets these observations differently. Just like people see colours differently or hear music differently. All of these things are submersive experiences.

And talking face to face is predicated on developing a close and trusting friendship, a rapport, indeed the earning of permission to make the recording in the first place. This takes time, which is why fieldwork often requires extensive periods of work in sometimes difficult conditions.

Because we conduct research in the field, rather than in the controlled conditions of a laboratory, there are plenty of variables, which is why we talk to a number of people, rather than limiting to just one individual, to try to get a handle on what is going on in their lives, and the diversity of experiences that even members of the same community may hold.

Sometimes we collect information by a questionnaire list; but most often the ‘interviews’ are very informal (though, as I have said, they are formally recorded), open-ended and often require re-engagement on multiple occasions, especially when returning to a community after a break.

Anthropologists invariably return repeatedly to a community, particularly (but not only) when studying social change, but as every aspect of any culture is constantly changing (language, customs, kinship, religious practices, etc.). This is how we measure change over time. We call this a ‘diachronic’ approach, which is unique to Anthropology but has now been borrowed by other related disciplines like History, Sociology, Politics and Geography.

The other approach is ‘synchronic’, a snap record ‘of the day’, commonly through the administration of a questionnaire. The National Census is an archetypal synchronic project—a record of a day in the life of a country.

THIRD

People often ask how and why I became a museum-based Anthropologist?

I had always been interested in museums, and all the different objects they contained.

I remember my childhood when Mother took us to the Auckland Museum every school holidays. It’s also a War Memorial, but it’s not a War Museum per se; in fact, it holds the largest collection of Polynesian (including Māori) cultural materials in the world, as well as a lot of historical and other materials that reflect both the prehistory and history of Aotearoa New Zealand.

We each had our favourite items, and our favourite places.

The Planetarium was great, but most favourite of all was the great Māori Gallery, with its waka (canoes), pataka (storage houses), whare (homes) and whare rūnanga (meeting house) behind the marae ātea (the public concourse, or greeting ground) all in use, today, even within the Museum, as they were when we were children. It is tapu, sacred.

I remember meeting Mother’s ‘family uncle’, who was Director (or otherwise somebody high up, he was pretty important, anyway) of the Museum, one time when I was about 8 or 10. His name was Mr Scobie. I remembered his name earlier today (he was Scottish, I think).

Mother took me to meet him on one school holiday. I remember, quite vividly even today, sitting on a chair in his office, my feet not even half way to touching the floor, in front of this enormous wooden desk, and talking about (what I guess, now, was) Museology. It was an informative moment. He was very kind, and offered to show me some collections in storage, things that the public never saw, if only because no museum can display everything they have.

This was another seminal moment.

It all added on, one strand into the next, and another, and another, which has continued all my career.

FOURTH

So how did I end up at the Berndt Museum of Anthropology at The University of Western Australia?

Looking back, things in my life seem to have coalesced, to what seems to have been an amazing degree.

Interest initially in History, especially Social History, and in people, as in what I soon realised was Social Anthropology.

Bringing it all together.

I returned to Perth in 1974, following my initial fieldwork for my PhD at Mt Margaret, to commence writing up my PhD on social change. It was a long process. I went back many times, and continue do, as many Anthropologists still do. I’m now working with the grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, of those I worked with so many years ago.

Holding the pearl shell original of the Museum logo, at the Museum exhibition Relocate and Rediscover: Treasures of the Berndt Museum. Photo: UWA Cultural Precinct. 1st May 2012.

But during that period, Professor Berndt, ‘Prof.’, as we always called him (his wife and intellectual partner, Catherine, also an Anthropologist, was called ‘Dr Catherine’) asked me to ‘relieve’ in the recently established and then known Anthropology Research Museum in the Social Sciences Building at The University of Western Australia, in the absence on Annual Leave of somebody who turned out to be my predecessor, Sandra Carrivick, who was the second Research Assistant to have worked on the Berndt’s collection. This was in 1976 and 1977.

I remember very clearly that one evening at the Berndt’s, over a brandy, Prof. asked me what were my intentions: was I to return to Auckland, or would I stay? I told him I would like to stay. That I loved living in Perth.

The task was sealed.

I subsequently joined the new Museum, for the First Term as Joint Acting Curator with Sandra, and then when she took maternity leave, as Acting Curator until the end of the following year.

It took time for the Museum’s then Board of Management to establish a permanent position of Curator, for which I applied, and was appointed after two years Acting, at the commencement of 1978.

The truth of the matter is that I had realised, during my two years of annual Leave Replacement, while I was working on my PhD thesis, wandering around the Museum, looking at the items held there (‘personages’, Prof. and I always accorded them) and reading the catalogue cards, that museum collections could tell us a lot about the nature of social change in Aboriginal (and other) societies, a theme that had been uppermost in my mind since I commenced Graduate Studies at the University of Auckland.

It all came together. People and Community. Place and sense of Belonging. Sense of Country, Sense of Identity.

And that’s why I’m here before you now.

John E Stanton, 22 December 2021

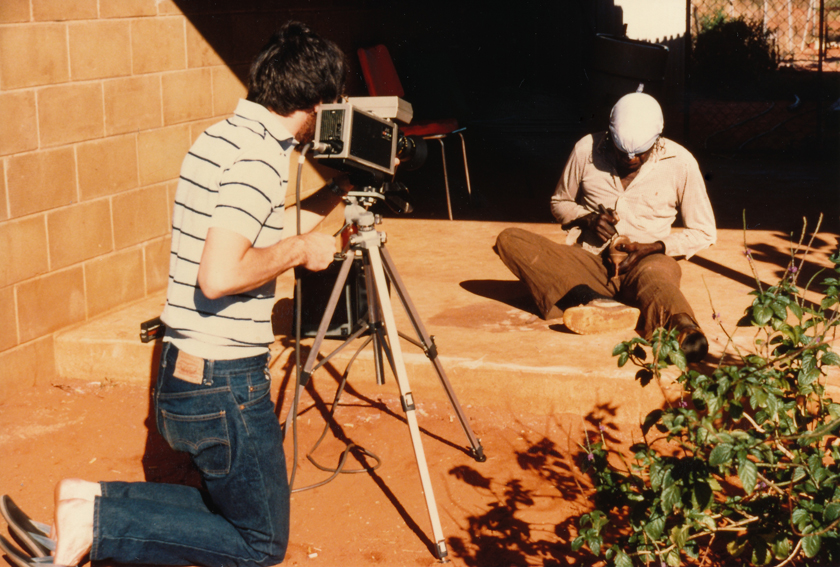

Video-recording with the ‘porta-pak’ Basil (‘Biggi’) Albert at Broome. June 1985.

With visitors from Goulburn Island for the Opening of the exhibition, Little Paintings, Big Stories: Gossip Songs of Western Arnhem Land. August 2013.