It is essential to consider the social, political and cultural context in Western Australia to fully appreciate the Carrolup Story and the achievements of the Aboriginal child artists of Carrolup. We have devoted early chapters of our forthcoming book – Aboriginal Child Artists of Carrolup – to this context. Here, we take excerpts from our book to illustrate one very disturbing aspect of this context.

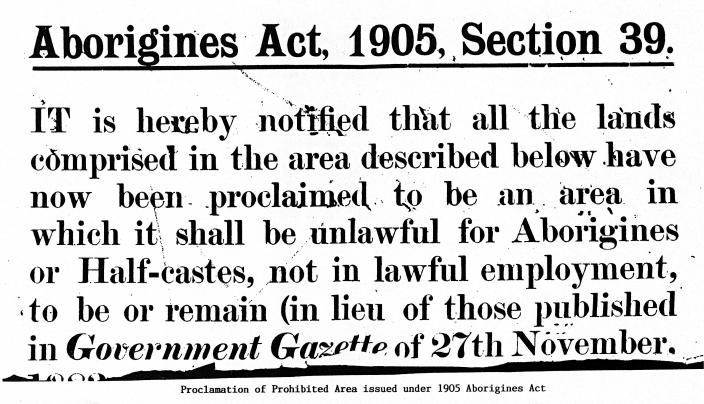

No piece of government legislation stirs more negative emotions in Aboriginal people of Western Australia than the 1905 Aborigines Act. The stated aim of this Act was to ‘make provision for the better protection and care of the Aboriginal inhabitants of Western Australia.’

Instead, the Act laid the basis for the development of a repressive and coercive state control over Aboriginal people in Western Australia, as described by Anna Haebich in her excellent book For Their Own Good: Aborigines and Government in the South West of Western Australia 1900-1940 (p. 83):

It set up the necessary bureaucratic and legal mechanisms to control all their contacts with the wider community, to enforce the assimilation of their children and to determine the most personal aspects of their lives. No provision was made for Aborigines to be consulted over decisions made on their behalf: they were simply expected to submit to these outside controls over their lives… Rather than promoting their advancement the Act drove a wedge between them and the wider community and served to hamper their efforts to make their own way of life.”

The 1905 Act created an Aborigines Department under the control of the Chief Protector of Aborigines, who reported to the relevant Minister. The Department was:

… charged with the duty of promoting the welfare of the aborigines, providing them with food, clothing, medicine and medical attendance, when they would otherwise be destitute, providing for the education of aboriginal children, and generally assisting in the preservation and well-being of the aborigines.” Section 4, 1905 Aborigines Act

The Act gave sweeping powers to the Chief Protector and to the honorary protectors he appointed to act in local districts.

The Chief Protector shall be the legal guardian of every aboriginal and half-caste child until such child attains the age of sixteen years.” Section 8, 1905 Aborigines Act

As legal guardian, the Chief Protector had the right to take any Aboriginal child from their family and send them to missions or other institutions. With the approval of the Minister, he was allowed to:

‘… apply to a justice of the peace for a summons to be served on the alleged father of such child for the purpose of obtaining contribution to the support of the child.’ Section 34(1), 1905 Aborigines Act

The Governor now had the right to declare any Crown land to be reserves for Aboriginal people, and to confine Aboriginal people to these reserves. Any Aboriginal person who refused to be kept within such a reserve was guilty of an offence against this Act. [Section 12 of the Act] The Chief Protector also had the power to manage the property of Aboriginal people, with or without their permission, if he deemed necessary. [Section 33]

The Chief Protector, and his local honorary protectors, controlled access to employment of Aboriginal people through a system of permits and agreements. They could become involved in the lives of Aboriginal people who were deemed not to be working properly.

Any aboriginal who, without reasonable cause, shall neglect or refuse to enter upon or commence his service, or shall absent himself from his service, or shall refuse or neglect to work in the capacity in which he has been engaged, or shall desert or quit his work without the consent of his employer, or shall commit any other breach of his agreement, shall be guilty of an offence against this Act.” Section 25, 1905 Aborigines Act

Police and justices of the peace were granted special powers over Aboriginal people, which resulted in a great deal of injustice. They could, for example, order ‘loitering’ or ‘indecently dressed’ Aboriginals to leave the vicinity of towns.

The police had the responsibility to lay charges against Aboriginal people offending against the Act, and they did not require a warrant to make an arrest. Harsh penalties – sentences of up to six months imprisonment, with or without hard labour, or fines of up to £50 (equivalent to over $7,000 today) – were imposed by local courts to ensure compliance with the Act.

The Aborigines Department relied on local protectors to ensure that the Act was enforced, attend to the welfare of local Aboriginal people and represent them in court, provide the Department with statistical information and reports on individuals, and deal with a variety of other matters related to local Aboriginal people. No checks were made on the suitability of people to become local protectors. Police constables and even private citizens took up these roles. No training was provided.

As the police were local agents for the Aborigines Department, in addition to enforcing the law, they were both protector and prosecutor. Not surprisingly, many policemen saw their role as law enforcers much more important than their welfare duties. Promotion for the police was not dependent on the sympathetic treatment of Aboriginal people, but on the number of arrests and prosecutions.

The Aborigines Department had virtually no power to influence the way the police treated Aboriginal people, or to ensure that the regulations of the 1905 Act were being followed.

Some Aboriginal people used alcohol to dull the emotional pain arising from their traumatic experiences. Attempts to control access to alcohol by prohibiting its supply to Aboriginal people had proved difficult to enforce. Even if whites were caught supplying alcohol, they rarely faced more than a minimal fine. It was easier for police to catch Aboriginal people drinking, and charge them with an offence, then catch the person supplying the alcohol.

The difficulties that Aboriginal people faced in obtaining alcohol and escaping police detection encouraged drinking patterns involving the rapid consumption of alcohol.

The 1905 Act was intended to prohibit casual sex and long-term de facto relationships between Aboriginal and ‘half-caste’ women and non-Aboriginal men. However, police were often unwilling to charge white men for having sexual relations with Aboriginal women.

The most shocking element of the 1905 Act was that related to the removal of children from their families. This provision of the Act was not used extensively between 1906 and 1911, in large part due to the lack of funds to cover the costs of transporting the children and maintaining them in missions. However, this situation was to change dramatically when Mr A O Neville became Chief Protector in May 1915.