In my last two blogs you can see here and here, I have included sections of our book Connection: Aboriginal Child Artists Captivate Europe that described various elements of the colonisation process in Western Australia. Description of the colonisation process, which impacted so badly on Aboriginal people, provides a context to the story of the Carrolup child artists. Here is a further section of the book, describing Mr A O Neville’s role.

‘Mr Auber Octavius Neville was Chief Protector of Aborigines between 1915 and 1940, initially working under the Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. He was a bureaucrat of great determination who devoted his talents and energies to tackling what he perceived as an emerging racial problem in Australia. He did not just exert a profound influence on policy and practice on Aboriginal affairs in Western Australia, but also influenced related policy across the country.

Today, ‘Neville the Devil’ is remembered by Aboriginal people more than any other white person as being responsible for the tyrannical control that was exerted over Aboriginal people.

Mr Neville was appointed as Chief Protector at a time of growing animosity between whites and Aboriginal people, particularly in the South West of Western Australia, where the encroaching agricultural industry had led to Aboriginal people being forced off their land and marginalised as seasonal workers or dependants on government rations. An increasing prejudice towards Aboriginal people resulted in calls for them to be excluded from contact with white society (cf. Chapter 1).

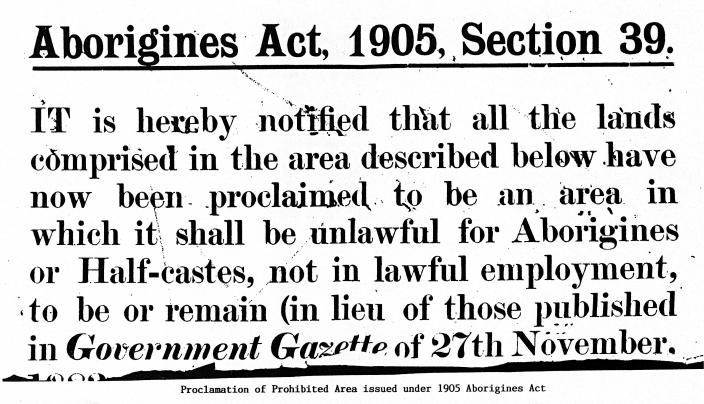

Neville’s appointment resulted in a period of strict implementation of the Aborigines Act, 1905, and unprecedented interference in the lives of Aboriginal people, particularly in the South West. Neville was a skilled administrator who developed a systematic set of records related to all aspects of the life of Aboriginal people. His practice of keeping personal files on individuals enhanced his department’s knowledge of, and control over, the lives of Aboriginal people. He undertook regular tours of inspection throughout the state and had a large network of local protectors (72 in 1919). To Aboriginal people, he was a symbol of authoritarianism.

In the early years of his position (1915 – 1920), Neville focused on the development of the government-run ‘native settlements’ at Carrolup and Moore River (cf. Chapter 1 for more details). The idea of these settlements was to isolate Aboriginal children from their parents, then educate and train them for unskilled occupations, e.g. domestic service and farm work. These settlements would not only serve the purpose of giving Aboriginal children the ‘opportunity’ to shed their Aboriginal background, but would also appease white communities who did not want Aboriginal people camped on the edges of towns.

Another important aim was for these settlements to be developed with the minimum amount of government expenditure, which is what happened. The settlements became places that had shocking living conditions, harsh controls and cruel punishments.

In 1916, Neville introduced a scheme where employers had to purchase permits and agreements to be able to hire Aboriginal people. This innovation later acted as a disincentive to many potential employers to hire Aboriginal people, particularly during periods of economic depression. Neville also encouraged employers to forward part of Aboriginal people’s wages to the Department to be deposited in individual Trust Accounts, so that wage earners and their dependants could be paid in a ‘regularised manner’. Many Aboriginal workers later claimed, justifiably so, that they were never paid.

During the 1930s, there was a further growth in racist attitudes towards Aboriginal people. Racial prejudice, especially towards ‘half-castes’, was paraded as ‘the Aboriginal problem’. People were particularly concerned with the growing number of ‘half-castes’. In 1901, there were 951 ‘half-castes’ in Western Australia; by 1935, the number had risen to 4,245. Beliefs entered around Social Darwinism were influencing an increasing number of people, including Mr Neville, who was worried about the emergence of an ‘outcast race’.’

CONNECTION: Aboriginal Child Artists Captivate Europe. David Clark, in association with John Stanton. Copyright © 2020 by David Clark

You can read more here in the Prologue of the book.